What Streets of Rage 4 taught me about life

A.K.A. Work through the suck

(15-20 min adventure)

For the record: I’m terrible at fighting games (so don’t challenge me). I hail from the nomadic tribe who button mash until I find a move that looks kinda cool, and then slam it repeatedly whilst hoping for the best.

As such, Streets of Rage 4 was an interesting learning experience. The curious (and initially annoying) thing about the game is that, every time you finish a level, it tots up your score of how well you kicked butt and how much you got your own butt kicked, and gives you a grade. It was the standard set of most games: A-E (much the same as most educational institutions) with a special ‘S’ grade for the particularly awesome. As it matches my first initial, it’s a decision I’m always down with.

Considering I’d get ‘Game Over’ on level 1, I’m sure you can imagine my grades weren’t much to write home about. Assuming I could even muddle my way through a level, I’d sweep my brow and be awarded a sad-looking ‘D’ grade for my efforts. To be honest though, it was an annoying distraction. I don’t care for leader boards or high scores; I was here to enjoy the game… a decision for which I count myself quite lucky (more on this later). What was unexpectedly interesting, however, was seeing how the grades changed the more I played the game. It was at once completely obvious and rather surprising.

Lesson 1: The myth of The Zone

Do you know what I’m referring to when I use the phrase “Being in The Zone”? That point where you just seem super focussed and things seem to fall into place? Maybe you’re a musician, and that infectious riff has just hit you out of nowhere. Maybe you’re landing all of the right moves at your favourite sport. Or you’re even just having one of those days at work where things just go your way. Those moments.

Sometimes I had those moments during Streets of Rage 4. Through my muddled D and C grades, I’d sometimes get a level where I just seemed to be “on it”. I’d pull off some dazzling looking combos and back-kicks. I had that inclination of “this might be the level” and, lo and behold, would walk away with a pretty ‘B’ grade.

Now on the flipside, do you know when you have an off day? When things really don’t go to plan?

I had those too. Even after a few months of playing, I still had sessions where I’d decide that the best way to handle a flailing wrecking ball was to stop it with my face. I’d slug it through, desperately looking for conveniently-placed health pick-ups (maybe popping in the odd expletive) and would ultimately be happy to see the end of the level. The grade I left with?

It was also a ‘B’.

To make things stranger, I need to tell you about Max.

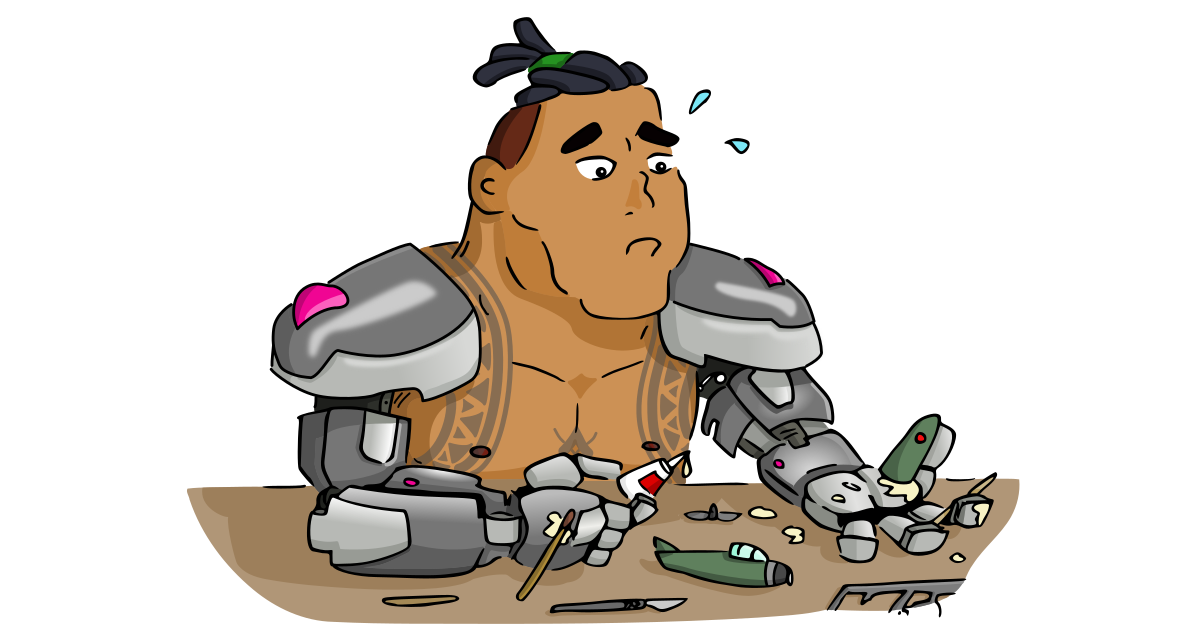

I hated Max Thunder. He’s a hench pro wrestler who waddles around like he’s constipated and throws punches in a painfully-slow arc like he’s impersonating a Ferris wheel. I gave up all hope of trying to play well, and conceded to just trying to finishing the damn game with him. As I waddled my way through the levels, I’d generally see his unimpressed fizzog at the bottom of the leader board. Get over it, Max.

I finally made it to the last level, ploughing through everything whilst meeting the service end of a mace. Max was at least good at that. Through a mix of dumb luck, grit and hefting my oversized bulk at every cluster of enemies that lined themselves up like bowling pins, I managed to slug my way through the final boss and, to great relief, closed the chapter on my Achilles-meathead.

What greeted me?

It was an ‘S’ grade.

It was literally the 3rd S grade I’d managed to acquire throughout the entire 40-odd hours I’d played. And there I was, looking at a big, shiny S on one of the tougher levels with my least-liked character.

The point of all this? The Zone and its supposed importance is, in my opinion, quite overrated.

If you’ve ever read up on motivation or studied any particular skill in depth, sooner or later you’ve likely run into the concept of “Inner Game”1; the idea that one of the key things that separates the winners and the losers is what’s going on in their head, more so than on the playing field. The ideas were a revolution in 1960, particularly with the publication of Maxwell Maltz’ Psycho Cybernetics and has since created a living for self-help gurus and life hackers everywhere.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not refuting that the right attitude and mental fortitude doesn’t make a difference. When you’re battling it out to acquire the top spot within the top 0.1% of the population, where sometimes even milliseconds are the difference between first place and a defeat, then, yes, a mental edge will probably make a key difference.

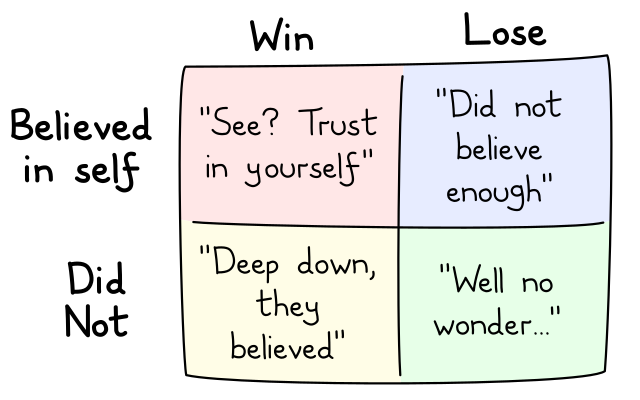

The problem I have is that it’s easy to get the wrong idea (especially the way more aggressive sellers try to advertise their “secrets”). We’re essentially told that unless you believe you’re going to win, you’re not going to. Unless we have our headspace in check, there’s no point trying as we’re only going to self-sabotage. If you don’t think like a winner, you will never be one.

And for a number of years, I believed this.

Though I’d acquired numerous experiences through my life to the contrary that made me doubt this, I needed it spelled out. The neat thing with Streets of Rage 4 was where every level finished with a score, there was no longer any room for my own interpretation to get in the way. I wasn’t gauging how good something was based upon how I felt it went. I got to see the cold numbers telling me. And they were excitingly uninteresting.

The “in the zone” moments of my early sessions were equivalent to the “fate is defecating on my day” moments a few months later. More importantly (and where Max comes in), there wasn’t a correlation with my supposed headspace either. The moments I aced it were not always the ones where I was feeling like a champ. Some days I’d hop on, feeling pretty chipper, and I’d walk away with a shiny 'S'. Then, in the same circumstances, I’d flail about like an upturned beetle and get biffed into a ravine. Whether early or late, in a good mood or a foul mood, whether I felt like a winner or down on my luck… none of these actually seemed to make a significant difference.

There was only one prominent factor in my high scores: The more I played the game, the more my scores climbed. That’s it. It would be very easy for me to spin the Max story with some kind of “oh yes, it’s because I let go of all expectations that I didn’t get in my own way and was able to unleash my inner potential like some kind of bitching Phoenix”. It’s a pretty narrative that lets me pretend I’m a secret prodigy, but it’s also a lie. What I have found so baffling is that there’s no pattern to me snapping up those elusive my S grades. Some days I get them. Others I don’t. Regardless of how I thought I was doing or what my mental space was like, it was more by virtue of continuing to play and enjoy the game that I got better and those grades became more common. Whilst this may sound really obvious, the point I really can’t emphasise enough is:

Don’t get hung up on whether you feel like a winner or a loser at something. Your best is not dependent on you feeling at your best.

What I believe is one of the key components of perfection is, quite simply: Luck.

Now “Luck” is a concept that seems to leave people antsy. It can be pretty intimidating to feel that the outcome of something partially rests outside of your control. It’s easy to lament “how can I feel hopeful if my actions might not determine the outcome?”

To that, I’d like to offer another angle: Imagine if, even when you’re feeling rubbish, you still had as good a chance as when you’re feeling at your best? Imagine if you no longer had to wait until you were feeling at your best, to get a chance at your best? Is this now a limiting belief… or a liberating one?

I confess, I had favourites in Streets of Rage 4 (Adam 4eva). So, because I secretly wanted their scores to sneak a little higher than the others, I’d shove a sacrificial character to get clobbered over a few practice levels in the way of a warm-up (sorry Retro Axel). But guess who walked away with the shiny 'S' and guess who head-butted a dustbin? The first one wasn’t always Adam (sorry Adam). Much to my pleasant surprise, I was scoring S grades by playing, not by waiting until I was in an S-grade mood.

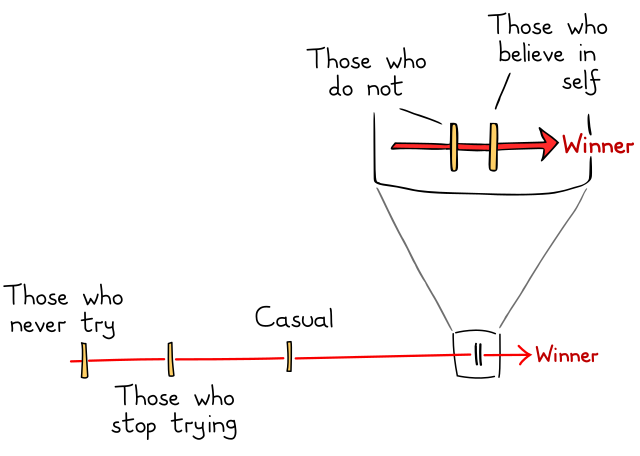

Imagine if I gave you a die and asked you to roll a 6, but warned you that a 6 only appeared if you truly believed it would. For the 5/6 who wouldn’t roll it, many would probably concede that they must not believe in themselves enough and would stop trying as they’re not going to win until they do2. Disappointingly, they wouldn’t simply pick up the damn die and roll it again. What I honestly believe sabotages a lot of people isn’t the thought that they’re not a winner… it’s the thought that not feeling like a winner is a good enough reason to stop trying.

I’d often think myself into a corner with this trap. I’d feel dispirited at a date not really going well, and basically gave up trying – telling myself “ah they don’t seem that into me", so I wouldn’t do things like message afterwards or ask out for a second date, as I assumed that I was bound for failure anyway. Being defeatist wasn’t what got me though. It was the thought that I would not stand a chance because I was feeling defeatist.

Similarly I might have a set of piano drills where I kept clipping the wrong notes or blank on patches altogether. 5 minutes in and I’d feel the tug of “looks like this might not be your day, so everything is going to sound rough from here on in. You should probably hang this up and come back later”. In the patch where I started entertaining this idea more regularly, I very nearly ended up not coming back to the piano at all.

Disappointingly, all of these were valuable experiences that I gave up on because I told myself that, unless I believed in myself, it wasn’t worth trying. It’s easy to fall into the trap of ‘fair weather practice’: Only trying things when the conditions are perfect or you’re in the mood. Telling yourself that, if you’re not really feeling like it, your output is going to suffer and therefore wouldn’t be worth the trouble. Why risk ruining something to a bad mood when you can wait for a more opportune time?

To me, when you hear things like the need to “believe in yourself”… It’s not about thinking that you will win. It’s about thinking that you’ll probably win eventually, and thus the sensible thing to do is to keep creating the opportunities for luck to eventually show up. Pick up the dice and roll it again.

My best moments have often not been at my best moods. I’d previously look at the “in the zone” moments of perfection in my life, assuming that my mood contributed to the outcome. But I now wonder how much of it was more the other way around.

Lesson 2: The myth of Hacking

Now luck, of course, isn’t the full picture.

The other strange bit about those S grades was, not only how randomly they appeared, but how the few patches where I actively tried for them often reaped nothing. I’d seen a few discussions on the game asking for tips on how to get those elusive top ranks. Within it, people were often sharing horror stories of how some levels took 100-200 attempts to snag it. Imagine that? Sitting and trying the same thing hundreds of times to get it just right.

Imagine then, my surprise when I casually snagged an 'S' on that same level during a playthrough. Believe it or not, this isn’t a humble brag (ok maybe slightly). The reason this piqued my interest was that, had I attempted to pull this off earlier in my tenure of playing the game (when I was less experienced), I likely would have been in the same 100-200 attempt boat.

And that’s the bit that interested me: I was able to accidentally achieve something on the first attempt, which would have taken me hundreds of attempts just a few months earlier.

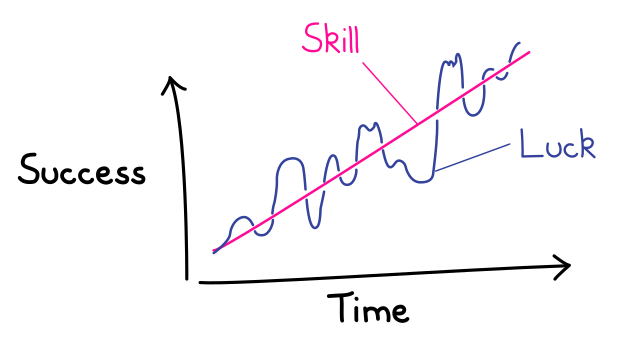

Whilst luck (and re-rolling the die) have their parts to play, the other key element to not overlook is the more obvious one: Skill.

Skill gives you your benchmark and luck is what creates fluctuation around it. The reason this is important is that, yes, creating more opportunities where luck can appear is important… but you also need to pay attention to where your skill is as well. Grounding your expectations is just as important.

The reason I count myself lucky that I sought to enjoy the game, more than master it, was because it inadvertently did just this. Because I didn’t seek to master the game, the patch where my skill sat below realistic S grades did not bother me. I knew that I’d have good days and bad days. Bad levels were put down to experience as I moved onto the next one. It was just part of the experience.

Had I approached the game with the intention of mastering it, however, I could have come unstuck. Every lower score would have felt like a failure and I likely would have been drawn into playing levels repeatedly until I cracked them. The trap of not moving onto the next level until I had got this one perfect. Maybe that approach would have meant I’d have mastered the game long ago. But do you know what would have been more likely? I’d have become immeasurably frustrated and stopped playing.

There are challenges in the game that I’d like to best. But I’ve purposefully held myself back from actively trying for them because I know that I’m simply not good enough yet. To try and shoot too soon would create more frustration and require those 100-200 rage-filled attempts to crack. That’s even assuming I’d have the patience for it. Instead, I’ve simply sought to keep having fun and exploring the game and, lo and behold, one by one, I’ve been landing them as I get better. And, yes, seemingly at random.

And now for the big “ah ha!” moment where I steady my top hat, swish my cape and swing the spotlight around to show why this is relevant.

To anyone out there who is creative, how often have you sat on a piece of work – a book, a song, an idea – but have never moved beyond it because it was never quite good enough in your eyes? How many of us are guilty of holding back until we feel that we’ve got it just right? That everything has aligned and there is no more we can do to better it. How many of us haven’t asked out that person we like because we were never satisfied that the time was right or the moment was good enough?

How many of us have stopped trying because it wasn’t perfect?

You may have heard of the term “The Wall” (No, not the Pink Floyd album). It’s the infamous phase most hobbyists go through (particularly musicians) where your expectations outgrow your skill and you get fed up, feeling like you’re just not getting anywhere. It’s deeply frustrating and, sadly, often the death-kneel of many aspiring hobbies.

To me, all of these problems aren’t a question of skill (or lack of). It’s a problem of misplaced expectations. It’s wanting things to be perfect before you’re reasonably able to do so. It’s setting the bar so high for your - sometimes even first - attempts that you never let yourself pass them because they never live up to what you hope they could be.

The big trap that I think gets people is: If you sit and labour over a hurdle until its perfect – you risk burning up all of the motivation you have for it. Worse, by never moving beyond that one hurdle you’re toiling over, you risk never reaching the others behind it which would give you valuable practice… practice which would ironically make that first hurdle a cinch.

There was something important I noticed in Streets of Rage 4 between eating apples and braining kickboxers with a guitar. Getting the high grades wasn’t a question of mood or headspace. It was skill and luck. As skill climbed and helped elevate the overall benchmark, luck still had its part to play. Some days I’d nail it. Others I’d be possessed by the ghost of Max and lazily flail at thin air whilst a cricket bat flew at my head.

Naff as it sounds, perfection is more a waiting game. The more you play it, the more opportunities you create for it to happen, as well as building your skill which, in turn, makes those opportunities more likely. It’s not about angrily hacking away until either you or the challenge give out. It’s knowing that, as good and bad days come and go, the slow-burn of skill needs time to tick over in the background.

When you first start playing an instrument, your playing won’t be perfect. It happens. Even after years of playing, if you first start trying to learn songs by ear, they won’t be perfect either. The first songs you write yourself? Your first album? Yep, not perfect either3. The way to crack them isn’t by labouring over each step until it is perfect. It’s by pacing it so that you keep working at them. That’s not to say don’t strive until they are good… but ensure it’s a good which falls within your capabilities.

The breakthrough in my online dating wasn’t because I mastered the perfect first message. It was more down to sending out lots and lots of decent messages. That’s not to say I didn’t try to make them good – but I didn’t sit on them until they were word perfect. The silly thing there was there was little correlation between how easily the message lent itself to replies I received. Sometimes the bolt of inspiration worked – others, I can only assume that the ghost of Max intercepted it and changed to a question asking about their preference for spandex-clad men grappling each other. Ce la vie. But because I didn’t focus on each and every message needing to succeed… I didn’t lose motivation to keep trying either. It was that, which accounted for more than anything else in my opinion.

Compare that to numerous years of ominously hovering in the background whilst I waited for the perfect moment to ask someone out.

The key takeaway point here is:

Don’t waste energy trying to make each and every thing you do perfect. Accept that some outcomes will rock and some will suck. It is only through repeated attempts that those perfect moments will land.

Or, perhaps more simply:

Work through the suck.

Epilogue

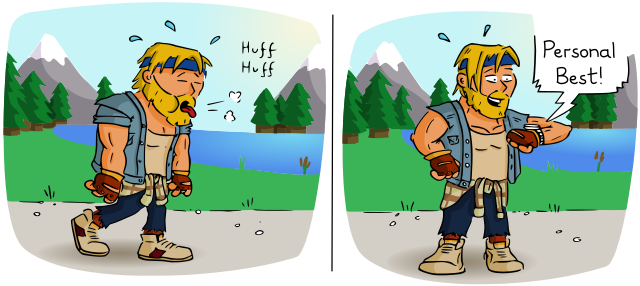

On the 28th August 2020, the day after finishing the first draft of this article, I acquired the last hard-fought S grade with Floyd Iraia. The funny thing about this was that I was in a foul mood, like, ready-to-pick-a-fight bad. Hopping onto Streets of Rage 4 for a tempo break, a couple of tries snagged it. I didn’t go in feeling like a winner, and even when I saw it I thought “wait… did I just do that?”

Squid and Whimsy

Squid and Whimsy