Your Inner Narrator

A.K.A. The brain is stupid

(15-20 min behemoth - Get comfy)

Do you know of your inner narrator?

It’s the one that maintains the awesome running-monologue throughout your life, also known as your “head voice”. You might know it as the calm observer who knows exactly what you’re really thinking.

Suppose I told you that there might be more to this bugger than merely reporting what it sees. That it might actually go one step further to actively back-rationalise everything you’re experiencing in order to maintain a clean, neat-sounding storyline. And it’s so good that you probably don’t even realise it’s doing it.

Intrigued? Then feel free to join me on a romp through split-brain psychology. You’ll need a saw, 10mg of suproxin and some trashy porn.

Cutting a brain in half might strike you as a bizarre idea.

But in the 1940’s, it was a desperate last-ditch attempt to stymie life-shattering epileptic seizures that were hitting patients multiple times a day. Between uncontrolled convulsions that could hit you at any time, throwing you into goodness-knows what risk, a doctor with a saw probably sounded like a rather peachy prospect. What was noticed during episodes was that the seizure would originate at a certain spot in the brain and, once it had reached to the corpus callosum (the bridge between the left and right hemispheres), would easily spread to the entirety of the brain. So the theory was whether cutting the connections would contain the overload to a single hemisphere.

Though the treatment never became commonplace (especially where less-invasive procedures have come about), it curiously showed a meted degree of success in 1962, after a patient known as W.J. showed improvements after the surgery.

But the cost of severing the superhighway between its regions was obviously that the left and right hemispheres could no longer communicate with each other. And it was this which greatly intrigued Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga, a grad-student in Sperry’s lab and now affectionately known as the grandfather of modern split-brain research.

They set to work showing W.J. a set of images. It was known at the time that images on the left side of a person’s vision are processed by the right side of their brain, and vice versa (why this curious quirk exists in animals is currently unknown). But with the corpus callosum severed, it was now impossible for either hemisphere of the brain to let the other know what it had seen. And that’s when things got interesting.

W.J.’s task was simple: When they saw an image, press a button and let the experimenter know what they had seen.

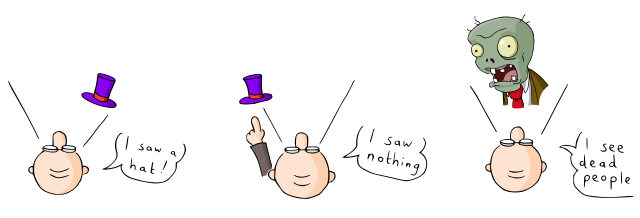

Images flashed to the right of their vision (and thus processed by the left hemisphere) had no problems. They dutifully pressed the button and explained “I saw a hat”. The left of their vision (so the right hemisphere) was different, however. They pressed the button on cue but, when asked what they saw, stated “I didn’t see anything”1. It turns out that the vital areas linked to speech are all sitting within the left hemisphere2… somewhere that now had no clue what the right hemisphere had seen.

But that didn’t stop their left hand - an entity also controlled by the right hemisphere - from correctly picking out the image when showed. So they knew what they saw… but the area of the brain which strings together words did not.

2. Even though the left side of the brain had no concept of what it saw, the right side could still point it out

3. Soil your plants

This was but the tip of the iceberg. A question still puzzled Michael Gazzaniga who, by 1981, was carrying the torch. The hemispheres did not appear to “miss each other”. From exchanging information on a daily basis to being completely separated, that would at least warrant 2 weeks of hiding in their rooms, mournfully browsing old photographs and listening to Coldplay. Patients weren’t complaining that an entire half of their vision wasn’t reporting for roll call. How come they felt so comfortably whole when they were carrying 2 entities which basically had no idea that the other even existed anymore?

It transpired that there was possibly more to the left hemisphere than first meets the eye.

In another experiment, a patient called P.S. was given a simple association task. They were shown some images and then had to pick the one that corresponded with what they had seen. A chicken was flashed to the left hemisphere. A snowy landscape to the right. From the collection of images to choose from, P.S. correctly picked out the chicken’s foot and the shovel. No surprises there.

Then they were asked why.

They replied “Oh, that’s easy. The chicken claw goes with the chicken, and you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed”3.

Wait… what?

What about the snow?

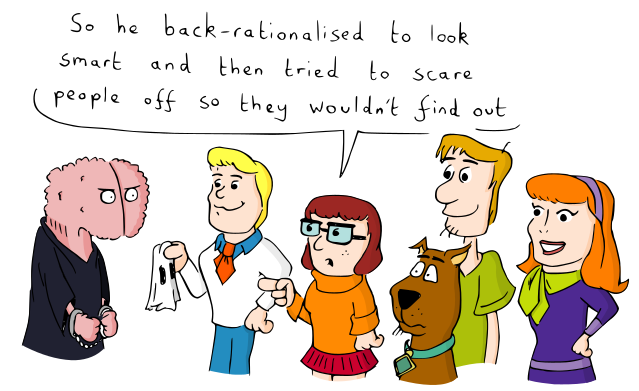

As we saw before, the left-hemisphere had no comprehension of what the right had seen. But it didn’t just leave it at that. It created a plausible-sounding explanation on the fly.

And this phenomenon repeated itself4. Anything given to just the right hemisphere appeared to be back-rationalised by the left-hemisphere, not aware that any form of instruction had actually been delivered. Patients being given cues to laugh or wave would explain that they found the experimenters funny or thought they saw someone they knew5.

What this suggests is that something within the left hemisphere of your brain (likely in the language modules) appears to create believable justifications for everything you do. Not only does it appear to create the running commentary we are likely used to, but goes as far as to fill in any gaps to make sure the narrative appears rational and seamless. This process is sometimes referred to as “confabulation”. In effect, we all may have an in-built PR machine quietly ticking away in the background.

This is likely why, despite studies proving time and time again that we’re dumb, impulsive and half the time have no idea why we actually do things, that we only ever really accept that truth for other people. To us, our choices almost always seem well-grounded and rational. That’s possibly because, just out of eyeshot, our brain’s working round the clock to make them look precisely like that.

Gazzaniga referred to this as the ‘Interpreter’ is his 1989 publication “Organization of the human brain”6. He suggests this might be responsible for the likes of panic attacks or phobias: The left-hemisphere making an incorrect association between a biological response (such as a fear response) and a trigger. But this could stretch even further. Could it also be the reason why our minds can so often be tricked into emotional states?

Still got the porn? Excellent.

In one study, male participants were given questionnaires by a female researcher… the catch being that some were asked over a small crossing, the others on a rickety foot-bridge over a 230-foot drop onto rocks. Afterwards, she gave them her contact details in case they “had any questions”. Of those on the small crossing, 2 of the 16 called back. Those on the rickety bridge showed a dramatically different result, however. A whopping 9 out of the 18 called later on7, possibly misinterpreting the heightened arousal from a precarious situation as sexual interest. Who needs negligee when you have certain death? And people say romance is dead. This is also precisely why dating circles suggest a horror movie or theme park as an ideal first date8.

In another study, a group were given an injection to test a new vitamin called ‘suproxin’. The naughty secret is that no such vitamin exists. It was actually just adrenaline, so would instil heightened arousal in those who received it. After the dose, the participants were left alone with another subject, secretly a researcher, who spoke either excitedly or angrily about the study. Brilliantly, those with the injection mistook their physiological arousal for either excitement or anger… whichever one was presented to them!9

In other words, their physiological response was being mistakenly attributed to something that made sense. Their inner narrators appeared to spot the change, then made sense of it by picking the best fit from whatever cues it had to hand. Specifically, the other person in front of them.

“Goodness I’m feeling worked up… that guy speaking clearly seems irate about how the study is being carried out. I must be annoyed by it too then. Yeah, that makes sense. Screw this experiment! Someone get me a blowtorch!”

But the interpreter is no chump. You see, there was a third group in the suproxin study. Those who received the injection but were warned of its possible side effects; namely an increased heart rate and blood pressure. They were told why they would experience a physiological change.

Their response? Nothing. In fact it matched the control group, who had no such injection at all. You could emotionally prime them, but if they knew about it they didn’t take the bait. The interpreter already had the explanation it needed, and thus was not fooled.

But if you want something a bit raunchier (because why not), let’s finally put that porn to good use. In Joanne Cantor’s study in 197510, a group were given intense exercise and then made to watch a naughty movie, rating how much they enjoyed it afterwards (‘made to’ is perhaps a misleading term here). The group who watched immediately after their burst of exercise had pretty much the same verdict as a group who had fully recovered from it: 28-31 out of 100. Having literally just finished exercising, they knew that the heightened state of arousal was due to exercise, so thought nothing of it. Again, the group with a clear reason for a physiological change did not behave differently.

Hilariously though, this wasn’t quite the same for a third group. It turns out that there’s a window several minutes after exercise where the body feels like it’s calmed down, but is actually still in a state of heightened arousal. Can you guess what happened when this group watched the film during that window?

52 out of 100, that’s what. A veritable smorgasbord of genitals! Nearly double what the other 2 groups had rated.

There’s a reason I’ve detailed these and why I find them so fascinating – beyond deviant sexual tastes (hilarious as it may be). It’s the quirk we saw most in the suproxin study: If your inner narrator latches onto an incorrect theory, it won’t just misattribute the past… but will go as far as to continue to act upon it without you even realising.

But what if it’s wrong?

I used to get snappy and irritable after working on the computer. If asked, I’d nominate an annoying problem, a game being unfair or someone interrupting me… never my posture. But that’s precisely what it turned out to be. My setup at my parent’s house was shoe-horned onto a set of cupboards with no legroom, creating a rather hideous posture when using it that would inevitably leave my upper body tense. The best bit was that it wasn’t just me; anyone who used it became tetchy as well… but it never clicked. It sat for years under the radar, not being addressed, because we were all attributing the tension to more readily available targets. The ‘Grumpy Desk’ was a phenomenon that went unnoticed for around 6 years before I finally built a perch to let me sit like a real person.

We can comfortably accept that we may misjudge a person or a situation (i.e. an external event), but we likely don’t apply this to our own feelings too. This, to me, is the catch with introspection that no one warns you about. It’s all fair and well asking yourself why you feel a certain way… but that doesn’t always mean you’ll get the correct answer.

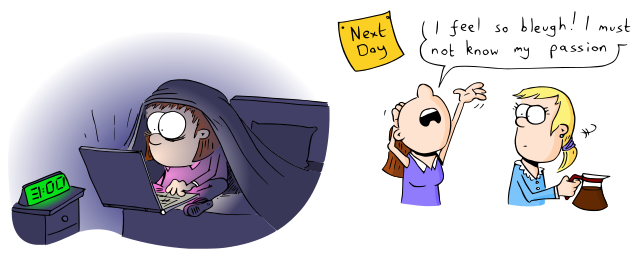

Perhaps we ask why we’re feeling a bit off today. In sensing ennui, we start prodding about to try and find out what’s missing in our lives. Maybe we conclude things like ‘lack of meaning’ or ‘not knowing my passion’, driving ourselves crazy over the notion that we might be letting our lives drift astray… when it could purely be tiredness, hunger or the body simply maintaining a baseline mood. And the worst bit? In trying to address what we think is the problem, we can end up exacerbating the real issue.

Let’s say your poor sleep pattern is creating a low mood, but you believe it’s because you’re not doing enough with your life. The remedy might appear to stuff your routine with even more things and stay up late trying to cram everything in. The result? Your sleep (the very thing you need to address) is further damaged as you pursue what you believe is the answer. This is a mistake I have made far too often to count.

Or what if the question is something like “why do I feel tense / anxious?” What could one of many innocent reasons is, instead, meticulously dissected to root out a rational-sounding explanation from the local surroundings. “It must be the people around me.” It muses. “I must be getting anxious because of them. Well one of them is looking a tad grumpy, so maybe I’ve upset them… oh heck, it must be that thing I said the other day! Crap, it’s totally that isn’t it!? They must really be annoyed with me…” boom. Before you know it, light tension distorts into paranoia.

In other words, not only can we exacerbate existing problems, we can end up fabricating entirely new ones too.

Is this all intentional? It seems puzzling that the brain might appear to get tricked so frequently by the body’s own physiology, considering that it shares a room with it 24-7. Whilst impossible to say if there is trickery at play here, let’s head back to the rickety bridge. If the brain doesn’t appear tricked when there is an explanation readily available, how come so many more of the men called back later despite having the 230 drop right in front of them?

It could be that they didn’t realise the effect that the precarious situation had on them. It could also be that being aroused by an attractive interviewer is a more interesting story than being scared. Put another way, if the brain is given enough wiggle room… would it go as far as to pick a preferred explanation if it can get away with doing so?

This might be why, perhaps, with the split-brain patients, P.S. explained that the shovel went with the chicken but W.J. said they did not see the hat. P.S. had room to manoeuvre, what with an image they could try and align their behaviour to. W.J., on the other hand, had nothing to work with.

And that’s where I feel psychodynamic theory can particularly get dangerous. Freud may be correct in suggesting that the conscious mind might fudge details, but have we incorrectly assumed that the subconscious isn’t playing the exact same game? Far from an untapped well of truth, the subconscious could be just as bad as our conscious minds. If you keep prodding it with the insistence “come on now, there must be some reason from your childhood that would explain why you’re having trouble with relationships nowadays…” it can end up twisting facts, misremembering events or, worse, completely fabricating stories of child abuse that you later realise did not happen11.

Whilst this might seem like a somewhat disheartening state of affairs… an inability to trust what you even think. There’s a reason these studies and the understanding of the interpreter is perhaps my all-time favourite discovery to come out of the scientific world. The second curious quirk that we saw.

Once your brain knows it’s a lie, it’s immune to it. Your interpreter isn’t strictly trying to mislead you, it’s simply making the best it can from a limited pool of information (possibly with some self-aggrandisement if it can get away with it). Once you feed it the correct information, however, it revises its stance accordingly.

One extreme example of seeing this in action was, curiously, seeing it play out on a good friend of mine.

I was meeting them for dinner and, a few cocktails in, started waxing lyrical about the above studies and the interpreter (yes, discussing science is my equivalent of ‘oh man! There was this one time…’). Upon explaining how the brain can make up problems where there are none, I weirdly saw a wash of relief sweep across his face. “It’s interesting you mentioned that” he mused and went on to explain that he had been anxious for the past couple of days but couldn’t work out why. He had recently attended a school reunion, where talk of his first girlfriend came up. Despite being happily married, he suddenly found himself unusually troubled by this distant memory and for much longer than you normally expect to.

What hadn’t occurred to him was that he had also had a busy week and poor sleep around the same time. And if there’s one thing poor sleep causes… It’s paranoia. So likely, the fleeting “huh, I feel bad about how that ended” was mistakenly latched onto the overarching anxiety caused by poor sleep and given the full blame for it. Seeing himself be so anxious about it then made it worse. That prodding sense of “why is this bothering me, is there something I’m not admitting to myself?”

But what was wonderful was that, as soon as this clicked, his face lit up and wore the relief of “it was just a dream”. It didn’t outright remove the anxiety he was facing, but it stopped him from twisting the knife, which appeared to having a bigger impact than the original “off” feeling he had. Needless to say, I was ecstatic and felt the need for another celebratory round of cocktails for the vindication of science.

And there is a reason to celebrate. Though the brain can be incredibly stupid at times, knowing this very penchant is sometimes enough to help mitigate these effects. I’ve had to remind myself of this often; frequently intercepting a possible rumination with the understanding that poor sleep, lousy weather or being incredibly hungry is the likely a larger factor for my state than whatever rational-sounding excuse I might have come up with at the time. It’s not that it wipes out whatever low mood I’m having, but it stops me from making it worse by needlessly getting worked up about it. I’ve unwittingly found out that there is such a thing as too much introspection.

And it’s an easy trap to fall into. Biology often feels too simple or naïve to really justify it. It can feel stupid to put down the bulk of a bad mood to nothing more than poor sleep or crummy posture. A useful trick is to ultimately look at the simple things first. In effect, developing the habit of not listening to the first fancy, rational-sounding thing your mind comes out with. Focus on what basic needs you might be lacking, and then work from there. Rule them out before moving onto other explanations. If you’re tired, stressed or achy, your judgement might be impaired as to what it is that’s actually bothering you.

By the time you’ve ruled out the little things, one of two things tends to happen. Either you realise you were in a bad place and the gnawing issue turns out to not be such a big deal. Or it’s still a problem, but you’re at least in a slightly better headspace to deal with it.

But we’re getting there. Personally, I adore the fact that ‘hangry’ is now a term (anger caused by hunger, for the uninitiated). It’s a growing consensus that, sometimes, a bad mood is caused by something as simple as needing a meal.

We’ll always get tricked by it. Heck, if I make the mistake of having coffee on an empty stomach, I can sometimes suddenly experience agitation and anxiety, as if I’m about to have a heart attack. It normally takes a minute of unease before I realise it’s heartburn.

It can be annoying, because it’s stupid. But once you catch onto it, it can at least be funny. And more importantly, you can stop yourself needlessly getting swept up in it too.

Squid and Whimsy

Squid and Whimsy